de Velde

Wim Segers

His very own signature results paradoxically from his refusal of one overly flashy signature. A situationism in which the ever-changing problems that come with every new project, and not the ego of a designer, define the identity - and the look - of and object. And actually, creating an object is never an end in itself: “We prefer to develop total concepts, that allow us to follow up, together with the producer, all phases from product development to presentation, including even the chocolate on an exhibition stand designed by us.” Operating in the periphery, Wim Segers has helped to put numerous companies, and his own region, on the international map through this approach. Meet the winner of this year’s Lifetime Achievement Award: “As a designer you have to be humble.”

He talks fast, very fast. Affably. Quietly, without raising his voice. But confidently. Deliberately. Without uh's and ah's. Like he designs. And unvarnished. Averse to the ‘brouhaha’ and bling bling in the design world, Wim Segers advocates a no-nonsense approach, down-to-earth - emphasizing that values such as functionality and sustainability prevail. But he also quotes verses from Christian Morgenstern’s poem Der Aesthet, the verses that Gerrit Rietveld had printed under the seat of his iconic Red Blue Chair, to indicate that the chair was not just intended for Sitzfleisch (Seat meat), but for the Sitzgeist (Sitting spirit), pleasure that went far beyond physical comfort. Slumbering under the still water is a poet. And it can also be read from his designs.

ICONS – His oeuvre from the past three decades is strictly limited to furniture and other household effects. Things that should at least make our daily existence more bearable, like the coffins he designed after his sister's death. But in each of them also tangibly reverberates the childhood dream of ever coming up with icons like a paperclip, a clothespin, BIC or MAC. Things that are so ubiquitous and self-evident in their simplicity that one does not think about the design, transcending the Zeitgeist in a very accessible and democratic way, if only for 50 years.

TRUST - He also prefers to send his products to the world with a secret mission. A double life. They shouldn't just offer seating comfort, but build trust, also with the producer, as a stepping stone in a strategy that helps shape his entire company. An approach with which Segers played a key role in putting not just local companies such as Tribù, Vasco, Saunaco, Indera, or now also Todus from Czech Republic, but also the Limburg border area where he lives and works in Belgium, prominently on the global design map. And with the growing success, the studio now also has projects in countries like Israel, Portugal, Denmark, Italy, and the US.

EGO - That Segers nevertheless remained a bit of an unknown soldier to the layman, doesn't bother him. On the contrary: that’s how it should be, as a logical consequence of his working method. “As a designer you have to be humble,” he explains. “Starting from scratch every time, and solving problems that are specific to the project. These are always different. Every material has its own singularity. The same goes for production techniques, pricing, or target audience. It is the power of a good designer to be able adapt, to combine those elements, and to translate them into a strong product. I call this Situational Design. An ego that wants to put its own stamp or signature on the end result, just gets in the way.“ It might also explain why the long row of chairs bearing his name and set up in miniature in his studio looks so diverse. The absence of an overly flashy signature is precisely the signature of Wim Segers: “The ever-changing shape arises almost automatically from the ever-changing solutions to the ever-changing constellation of problems.”

SHINS - Which does not imply that Segers does not swear by principles, from aesthetic to ethical. Old school but without complexes he uses the forgotten concept of applied art to describe his work: “We must look forward, but cherish the past. Respect for craft is basic.” Different from the fine arts, that can kick people in the shins undisturbed, applied arts must provide tools that serve them. And because all the negative connotations of the word design (elitist, snobbish, and way too expensive) are all too often true, he prefers to talk about product development: “In many cases the designer is little more than a provider of a superficial aesthetic, poured over an object like a sauce. The product developer, on the other hand, must ensure that the object is correct in its entirety. Manufacturability and sustainability, the fact that it can defy time, functionality and economic relevance, including a democratic pricing, plus an ecologically and ethically responsible approach, are all qualities that cannot be circumvented today. They also must fit together like a puzzle. And only then does beauty arise.”

FACE – The studio’s research regularly delivers innovations, which it takes to pre-selected companies. But the majority of the orders come from the companies themselves: “In some of these orders the aesthetic takes precedence, aiming for a limited edition. But usually they come up with a package of other requirements regarding pricing, target audience, use of materials, etcetera. In those cases, the question how the design can be economically relevant for the customer is central. That the design must have a visual capacity and a good face, then remains a matter that is interwoven throughout the entire design process, but our furniture is also primarily for living, hanging, romping, or eating in, and not to be hanging in a museum itself.”

ZEITGEIST – No matter how complex a set of requirements is, Segers never experiences this as a straightjacket, but as a challenge: “The creativity lies in balancing in such a way within those well-defined criteria and limitations that you still have something very strong left. Because good ingredients - functionality, emotion or surprising shapes - do not guarantee a good dish. The art of cooking lies in the way you combine them. And timelessness is a heavy concept, but I try to purify every design in such a way that it is at the same time a child of its time and transcends that Zeitgeist.”

VOLLEY – His father was, next to Mayor, also alderman of Culture of his city of birth, Maaseik, and regularly organized exhibitions. That was one of the reasons why he had decided to study product design at MAD Faculty nearby Genk. Already then he was a typical team player, as captain of Noliko volleyball team, now Greenyard Maaseik, with which he won the Belgium cup in 1986. However, when the team won its first league title in 1991, Wim was no longer there. He was already too preoccupied by Studio Segers, which he had started with Rita Westhovens a few years earlier, she as a graphic designer, he as a product developer - after completing his studies with a thesis on a game system for children with disabilities.

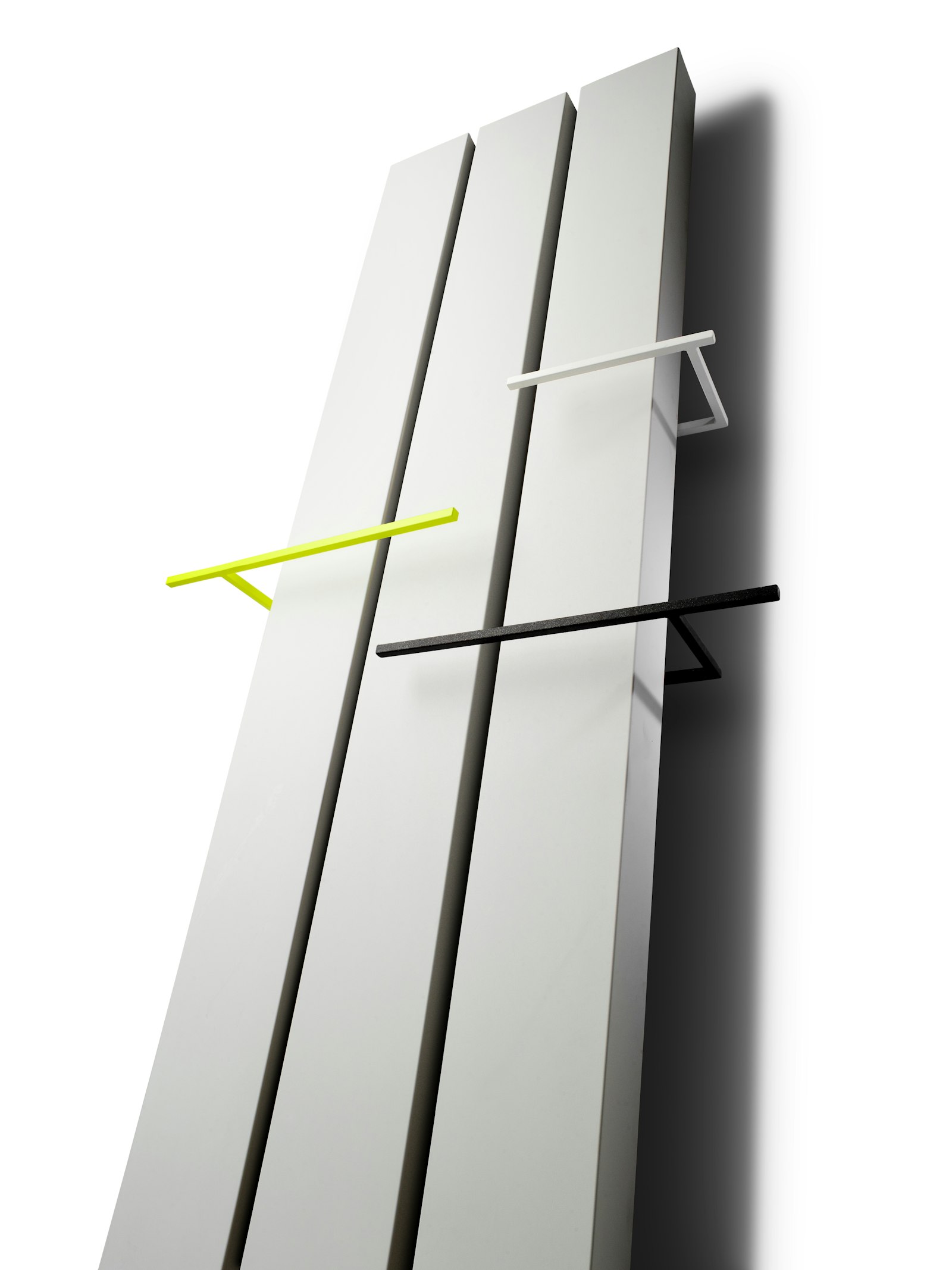

DILSEN - The dream of smart icons for the masses was already there then. But reality presented itself as Jos Vaessen from the town of Dilsen, who had founded the heating company Vasco in 1975, and asked them to design convectors. A proposition as tempting as the name suggests. For Segers, however, thàt was the challenge. The result was such that they became and remained home designers of Vasco, whose aluminum radiator program later won an Europese Aluminium Award and Ecodesign Award - mainly for its clear design.

BILZEN – One result was that Lode De Cock from another small town in the province of Limburg, Bilzen, came knocking. De Cock was a major importer of the then popular teak garden furniture: “Could we redo that Vasco story? Mid-nineties we created a first teak collection, a quite classic one. But I wanted to combine new materials and shapes: a sleek stainless steel frame with a seat in teak, “ Segers says. This is how Natal was born, a minimalist outdoor chair, and a milestone - in both studio and client history.

APPLE- Launched in 1999, Natal immediately won a Henry van de Velde Best Product Award ànd the Public Award. “This was especially unique for garden furniture, “ continues Segers. “And if you also consider how Lode has marketed those prices… .” For the company, meanwhile renamed Tribù, Natal - that grew into a collection with table, lounger, club chair, sofa, and more - was decisive in the rise to a global player, whose KOS-collection, also designed by Segers, is now even in Apple’s American headquarters. Natal was so successful that the design remained unchanged until 2010. And even then, except for some rounded shapes, only the stainless steel of the frame was replaced by lighter and recyclable aluminum.

MATCH - Tribù was followed by, to name just the most important, the Mecam Group (Moome, Indera), Saunaco, Wolters Mabeg, Younic, Vincent Sheppard, XL Boom, Deknudt, Kreamat, and Todus. But where any other designer would quickly turn to well-known brands in the wake of the growing success, Studio Segers preferably chose totally unknown and starting producers, from their own region. “It has to match somewhere,” says Segers. “Because our approach is such that we almost become permanent employees for the companies we work with. Sometimes there is no affection with the brand as it is at that moment. But if we notice that there is drive to take the label to a higher level, and we can add value, we like to think along with them. Well-known companies leave no room for that. And in Limburg there are a lot of entrepreneurs like Jos Vaessen, Lode and his son Koen De Cock, or Carl Meers ftom Indera who are fully aware that design is not just this sauce that is poured over products, but an intrinsic part of the production process and the development of a brand. And the fact that we are neighbors also has the advantage that we can constantly walk in and out of each other's company.”

IDENTITY - While Vasco and Tribù respectively grew into the more thoughtful, architectural, modern-classical antipodes of two other market leaders, Jaga and Extremis – “Without competing with each other, but by complementing each other. Very Belgian, that respect” - companies that started working with Segers usually developed an identity so clear that the essence can be captured in a few words. At the manufacturer of seating furniture Indera, the motto is 'modular and sustainable'; at sister company Moome 'compact, nomadic and affordable’, and at Younic 'unpretentious and artisanal'.

DAILY NEEDS - Looking at the evolution of the studio's output over the past three decades, one can only conclude that with increasing success, self-confidence also grows, together with the playfulness and elegance of the designs. And regret that the studio doesn't work for its own account more often, or doesn’t get more creative assignments, less bound to the package of requirements within which they operate in their more commercial assignments for companies. Projects in which Segers can give free rein to the poet and activist in himself. Lke the modernist coffins he designed in response to the exclusively bombastic market offer, the Step up chair, or Sketch- and BKRK chairs which the studio created for Bokrijk (BKRK). But above all there was Daily Needs, a modular system consisting of a chicken coop, rabbit cage, and bins for vegetable and herb cultivation, compost, and rain collection. After the closure of the local coalmines and Ford plant, which once were the local economic strongholds, the project had to give workers from the affected Limburg region the prospect of a new future. That the beautiful ensemble itself remained without a future, and is still waiting for a solid producer probably says a lot about the reason why the studio doesn't get involved in these kinds of freewheeling experiments more often.

PAVILION – Asked what job he would have done if he hadn't chosen product development, Segers does not hesitate: architect. And he's still committed to the old adagio anyway that furniture should serve architecture. It should therefore come as no surprise that, when a brand new 'creative pavilion’ for the studio was erected in Segers’ own backyard a few years ago, at the initiative of his son Raf (34) and his partner Chris-Laurenz Liesenborghs an architecture department was added, where Raf's wife, the interior designer Danielle Joosten, also works. Wim himself is flanked in the department product design by a second son, Bob (34), and Tom Fonteyn, while Rita was joined by Marjan Brants, Bob’s wife, in the graphics department. Studio Segers is still a family business, in the most literal sense of the word. Which again seems to fit perfectly with an output that focuses mainly on family matters with furniture and other household effects.

DOORS - Behind a blind facade in black-colored, artisanally lined concrete, and a huge glass wall alongside, houses a long corridor that connects three areas. Striking ànd telling: the rooms have no doors, whereas the meeting room in the middle serves as a daily platform for cross-pollination between the various departments. “Design is never the result of an egocentric process,” says Segers. “Ideal is a total concept for us, where we can closely monitor all phases of both product development and product presentation, with an approach that is situated at the interface with contemporary art, architecture, graphic design and fashion. Due to our diverse competencies, we are a complementary team. Together we cover just about the entire creative spectrum, from product design and photo styling to concept texts, brochures, websites, trade fair presentations, and showroom design.”

PASSION – For the family, by the family. Even the customers, whom the studio prefers to guide from scratch to become a global player, are considered family. But if those family sessions cross-pollination in the studio do not end up in cross & crass talk now and then? “More than once,” Wim beams, “And the close family ties ensure that no one has to hold back. That passion is also necessary if you want to come up with something that is right. And with so much youth around me, the work remains exciting. When you're a bit older, you sometimes work with the handbrake, because you know what can go wrong. But young people are much more difficult to slow down. That mix of routine and youthful enthusiasm is a bare necessity, just like in sports. And also with the customer it is often a fight, not only because of technical problems, but also because of the marketing. You must constantly dare to guerrilla against restrictions that could affect the value of the product. It is the strength of a good designer or studio to be strong in that.”

PROTOTYPE – It happens, of course, that the studio's contribution is limited to the initial design concepts. But usually technical drawings are made in collaboration with the client afterwards. At Vasco, Tribù, Saunaco or Indera, there is so much technicality involved in tinkering with the prototypes, that close cooperation with the customer's product development department is indispensable. “We learn a lot from such a collaboration,” says Segers. “But actually it's never just for us to do that product. It's so much nicer to be able to expand the project with a graphic concept, an exhibition stand, or a website. We even do the entire corporate identity for many companies.”

STOCKMANS - At MAD Faculty Genk, he was lucky enough to study with heavyweights such as Hugo Duchateau and Piet Stockmans. The latter is also discussed when we talk about the fact that, more than three decades after the founding of Studio Segers, and with the succession assured, the retirement age for both Rita and Wim is only a year away. “Piet is already eighty years old, but he remains busy more than ever. And during an architecture trip we got an explanation from Oscar Niemeyer. He was almost a hundred at the time,” says Segers, who looks much younger than he is. “So hopefully we're only halfway there.”

SITZFLEISCH – Meanwhile, times that are a-Changin’, crisis everywhere, and the call for more ecologically and socially responsible design, don't leave the studio untouched. And anyway, Segers has always wanted to improve the world, until, if possible, it would become one big happy family. The studio is currently not only working with pedagogically responsible toys, a project with which Wim returns, as it were, to the dissertation that marked the beginning of his career, but also with designs that are situated in the circular economy, such as Iquas: “As designers we have a social responsibility. The results of our work must be meaningful and sustainable. We find it obvious not to work with materials that are ecologically unacceptable. Of course we have less control over the production, but we always advocate that we make products that can be manufactured here. The competition from low-wage countries is of course enormous, but if you transfer the entire production there, you create even more unemployment here. Moreover, you never get the same quality. And a chair may be so comfortable for the Sitzfleisch, the Seat Meat, if it was created through child labour, you would not even want to take a seat there. It would be a sin against the Sitzgeist.”