de Velde

Sylvie Vandenhoucke

When you want to create an object, you always have to search for the possibilities that a material offers, for new shapes, for a new way of communicating, ...

There are only few people who search so intensively as Sylvie Vandenhoucke.

Everything started out with her training as jewellery designer and silversmith at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp, where she graduated in 1991. "A good choice", that's what Sylvie Vandenhoucke thinks, although she hasn't much work of that period anymore. At that time, her work showed already some features which we can still notice nowadays. Her final exam, about the topic 'Circles - Necklaces', consisted of a series of objects which did refer to the necklace, but which couldn't be used because they were obviously not wearable. With these two-dimensional works, she already gave them a spatial structure. However, the greatest enrichment of her trainingwas the feeling that she didn't need to be the best because she was the youngest among the other students, so not yet so grown-up and professional like the others. This mental freedom gave her the possibility to experiment, to go her own way. Another advantage of her training as silversmith - jewellery designer was that it concerned a large training, which made her familiar with different techniques and materials. But at the end, she asked herself "What now?". After all, the jewels which she made weren't wearable.

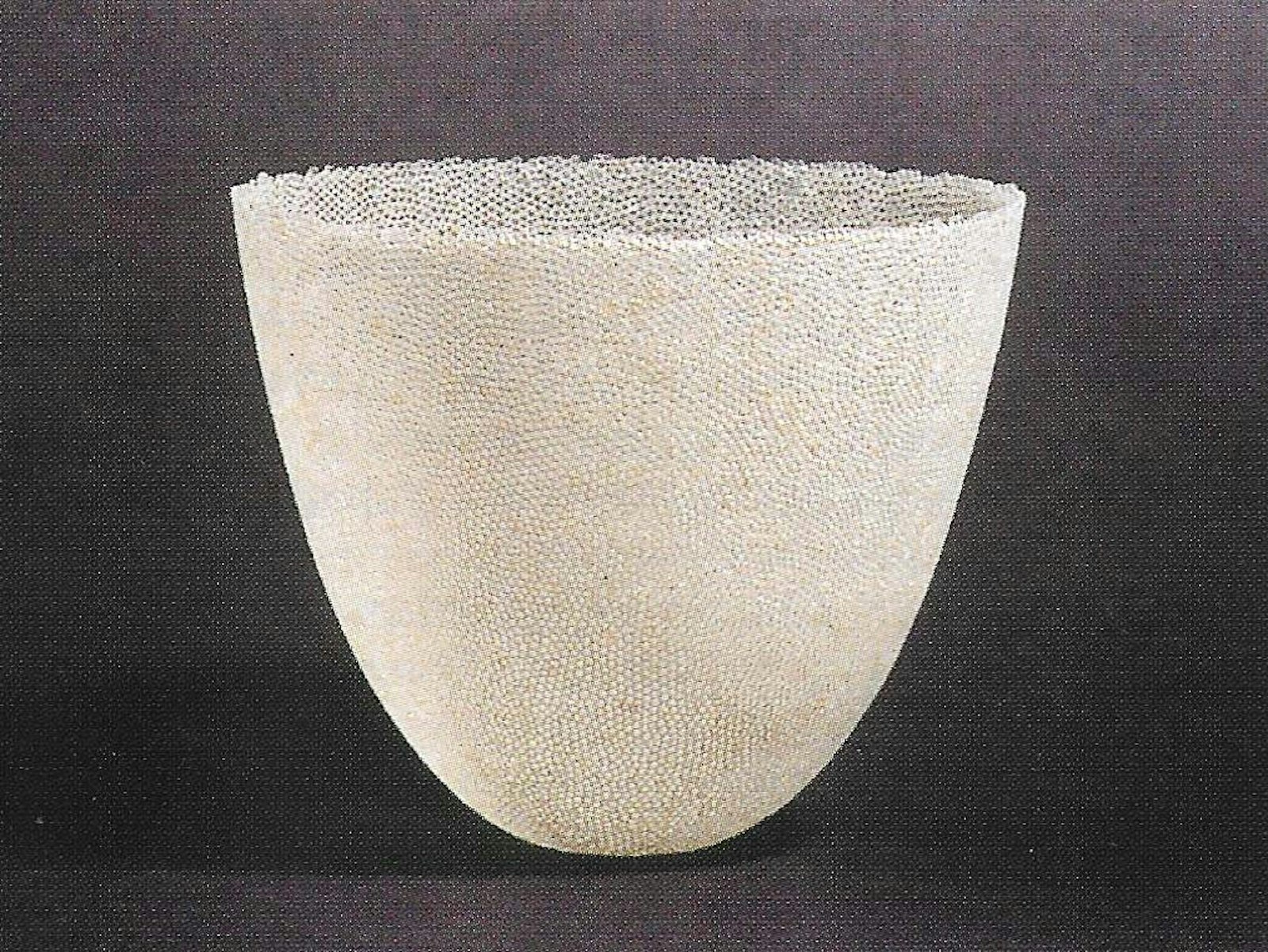

A long time before she began working with glass, she felt that pâte de verre kept possibilities in store for her. In the course 'history of the jewel', she already learned about pate de verre in a way to imitate gems, like lapus lazuli. During the last year jewellery design, she already began to integrate glass into jewels, because it becomes transparent and reflects light. That's why she quickly decided to take a glassware course at IKA in Malines. Also because it was again a training which gave her the possibility to learn and research different techniques. The result of this five-year course was a series of enchanting pot forms in pâte de verre with a wire covering the pots. Again, these pots were unusable. After all, it wasn't the function which was important, but the interaction between silver, glass and light. The melting process from glass molecules to pâte de verre captivated her interest and she felt that further research was necessary. She also wanted progress which she couldn't find anymore in her pot forms.

The solution was as simple as it was drastic: ceasing with the pot forms and following a Master Degree Glass at the London Royal College of Art. Only by not working in her own atelier anymore, she could avoid orders and she could really break away of the vase objects. During two years, she was able to focus on glass as material and on its features. She spend the first year especially on research of melting glass and metal to one material. During a long time, she only did research on white glass - which was before also the colour of her pot forms - and focused only on the melting action itself, not on the form. The result is a series of square facets, especially in grey and white with patterns. These facets give a certain graphical look to her work. The pattern, which is the result of cutting, pricking and engraving the wax model, refers to the engraving technique in the silversmith tradition and to the etching and engraving technique in graphics. Also in these bas-reliefs, the game of light and shadow remains very important. The light is kept in the pate de verre and is given back to the space in a changed way.

The research of these forms and the melting of materials is far from finished. That's why the designer has started a Research Degree at the Royal College in 2001. Her research project wants to study the implementation of oxides in the initiating process of pate de verre by experiment and research, so that she knows where and how a material can be changed. The difference with the previous training is that glass isn't being melted with metal anymore, but with metal oxides. The parallel with the metal membrane of the pot forms remains the same, but on a different level. The metal oxides show a discoloration and that's what it's about. She sees the discolorations as a direct result of the creation process, in which the ingredients, firing and concept are very important. By studying all this very well and by sharing it with others, the glass art obtains a scientific knowledge which she misses until now.

Beside this scientific and educational part, the research has also a very practical part. The glass designer has to buy coloured glass with specialised glass companies, that often have a very limited colour palette. By researching and understanding colour in glass, the designer hopes to make an endless colour palette that is accessible in the intimacy of the own atelier and this by offering much lower prices than glass companies.

The samples in this research have a lot in common with the white bas-reliefs, but than coloured. Again, the rhythm and the pattern are very important as signs of the material intervention. The glass paste is again very porous, which seems to live in the right light, which seems to vibrate. The pattern gives the facets again a sort of spatial structure, which we can also see in the two greater textile works that she made in 2001 for the London Underground and the Old Coffee Distillery Rombouts. By cutting textile in the specific patterns, she created a game of light and shadow, of material, of space.

Sylvie Vandenhoucke has become what she is now because she wanted to do research, to know and share her knowledge and that's why she's a designer who lives for the glass art, with a scientific disposition. She'll always surprise us with new, fragile and innovative works.