de Velde

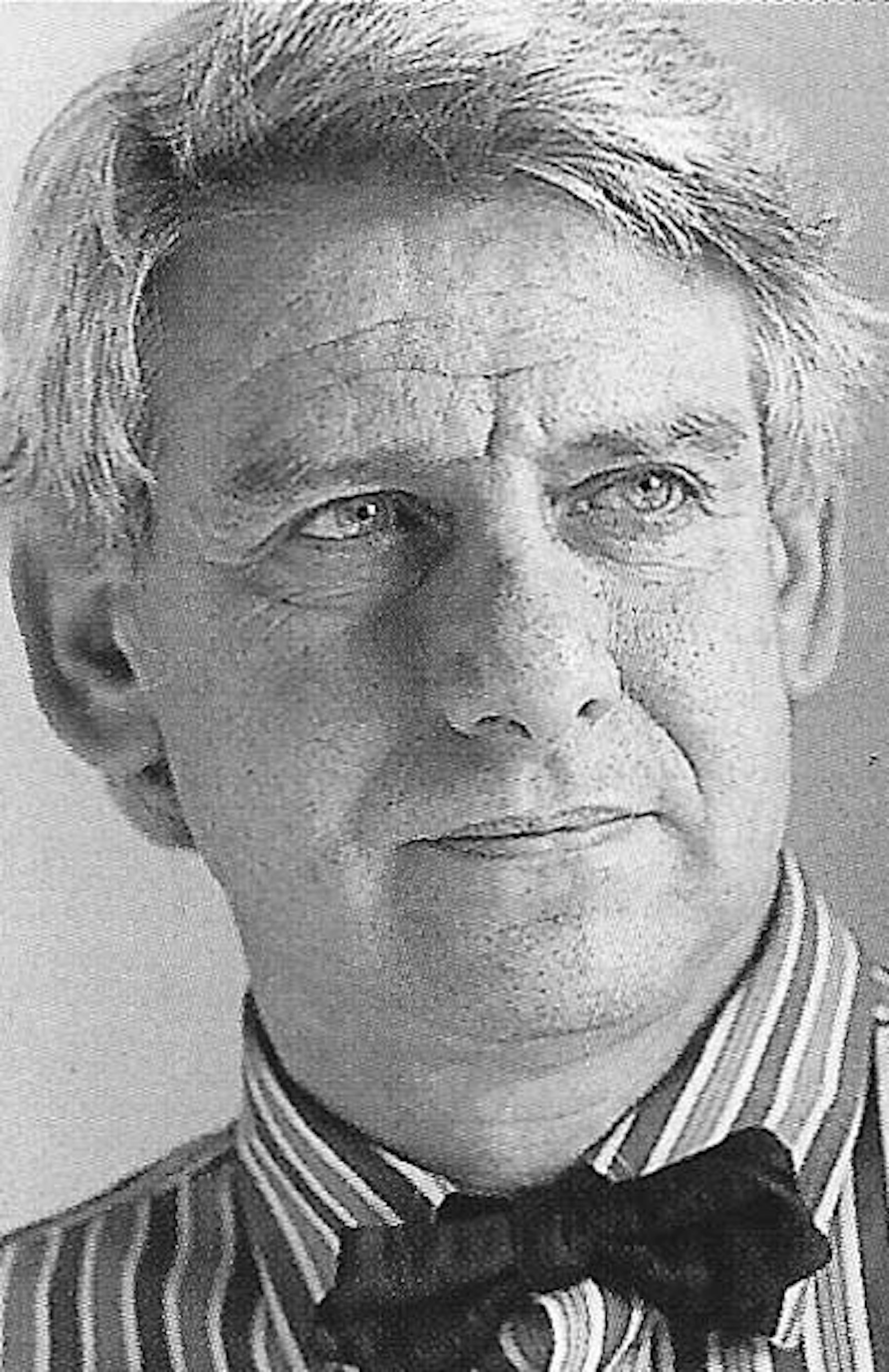

Piet Stockmans

Piet Stockmans (°1940) occupies a special place in the post-war production of artistic ceramics in Flanders and abroad because he approaches china in all its aspects: industrially, traditionally and visually.

Although he only became influential at a later stage, he has from the beginning of the sixties been in a position to experience at first hand the evolution of ceramic art.

When he graduated in 1963 from the Sculpture and Ceramics Department of the Provincial Higher lnstitute tor Architecture and Applied Arts in Hasselt and in 1966, as a modeller at the Staatliche Höhere Fachschule für Porzellan in Selb (in the farmer BRD), he was immediately employed as a free-lance at the Porselein- en Tegelfabrieken Mosa B.V. in Maastricht and three years later, he already received a teaching post in 'Product development' at the Municipal Higher lnstitute for Visual Communication and Design in Genk, where he was a teacher till 1998 .

He is the only industrial designer in Flanders along with Vic Goyvaerts (Arabia, Finland). During his 26 years at Mosa, he has designed more than 150 different pieces in china. Before 1969 and after 1983, he regularly designed household china and, in between these two dates, he produced hotel china. In 1967, he designed the stackable cup Sonja (1967) of which 30 million pieces have been produced, while in the meantime he also designed the most ingenious sets and services for hotels and institutions. His decoration-free white objects seem cool and businesslike. Yet, designs such as his multi-functional Passe-partout services and his breadboard, which enables the disabled to butter and cut bread with one hand, prove that creativity can triumph, even when designing industrial products.

ln 1987, Piet Stockmans started his own design activities under the name Studio Pieter Stockmans (independent of his contract with Mosa) and finally left Mosa in 1989.

He felt that as a designer, he was too dependent on other factors and moreover that he had insufficient control over the composition of the collection. Together with Henk Dressens, he then started his own factory in Genk which employed 35 people all trained by himself. In January 1992 however, technical and financial reasons forced the NV Pieter Stockmans Products to close its doors. During that period, the very successful and highly refined service series Expression (1991) was put on the market and since the closure of the factory, is being produced in Weimar (Germany) and sold by the Dutch company Indoor B.V .. This company also sells other designs by Stockmans, such as the Modus vivendi service.

Stockmans is regularly invited as a guest lecturer at home and abroad to discuss his work and on each occasion, he repeatedly states how much he considers his industrial work as being a heavy intellectual process, one of continuously re-evaluating the rules imposed ... while his free work always comes as a relief in which emotion, sensitivity and the tactile can be given free reign.

Although he has been making free work from the very beginning, we had to wait till the end of the seventies before he really came into his own as an artist. Since his participation in the summer exhibition Young Ceramists, Belgium 1980 at the Meeting Centre Scharpoord in Knokke-Heist, exhibitions have followed one another at an increasing pace. 1980 was also the year in which he bought his new oven, allowing him to experiment at his own workshop.

We can rightfully say that his breakthrough occurred in 1981 during the exhibition in the Provincial Museum of Hasselt, with the furniture producer ARTIFORT in Maastricht (the Netherlands) and in Genevilliers (France) where his first spatial installations were put on display. In 1983, he participated in the 17th biennial in Sao Paulo (Brazil). In October 1985, he was invited along with Frank Steyaert and eight ether famous ceramists from abroad to participate in the large exhibition Dragon Stone at 'The Art Gallery at Harbourfront' in Toronto (Canada) during the 4th 'International Ceramics Symposium'. The artists on display there were considered by all to be the leading edge of the international ceramics scene of that time. All participants shared a capacity tor being daringly expressive and highly individual in their use of the medium clay. Stockmans' four large wall installations and a floor installation created an impressive feeling of spaciousness. Because of the fresh, innovative and even revolutionary nature of these installations, Piet Stockmans was considered the odd man out at the exhibition.

In 1986, shortly after taking part in Toronto - which was an important step towards international recognition - he was asked to do his first retrospective at the Museum tor Decorative Arts in Ghent. Ever since, the interest tor his oeuvre seems to have become limitless. In 1988, he was awarded the Staatsprijs van de Vlaamse Gemeenschap voor de Beeldende Kunsten (State prize of the Flemish Community for the Plastic Arts). Stockmans' exhibition with Johan Van Loon and Jan Van der Vaart in 1991 at the famous Municipal Museum of Amsterdam, was also a milestone in his career. Moreover, several large museums in Belgium and the Netherlands started buying his work and he has been asked by some clients to integrate his ceramics into pieces of architecture. And as if that wasn't enough, he was also appointed Cultural Ambassador of Flanders in 1995.

lnnovation is the keyword for Piet Stockmans. In 1996 he began to design jewels for the company Niessing. In that same year he also received the Höchste Design prize in Nordrhein Westfalen for a new collection of dishes and goblets. Ever since the offers to participate in exhibitions are pouring in.

In the autumn of 1998, the Museum for Applied Art and Design in Ghent presented the Veni service which Piet Stockmans designed for Royal Boch.

At first, Piet Stockmans did not produce large-scale works. In fact, he first began by putting the rational dimension of industrial production into question in rendering cups unusable by changing them slightly, for example. Only later (by the end of the seventies), did he start to revolt against the impersonal aspect of repetition in floor and wall installations, it being the conditio sine qua non in industry where the object designed must be suited for mass-production.

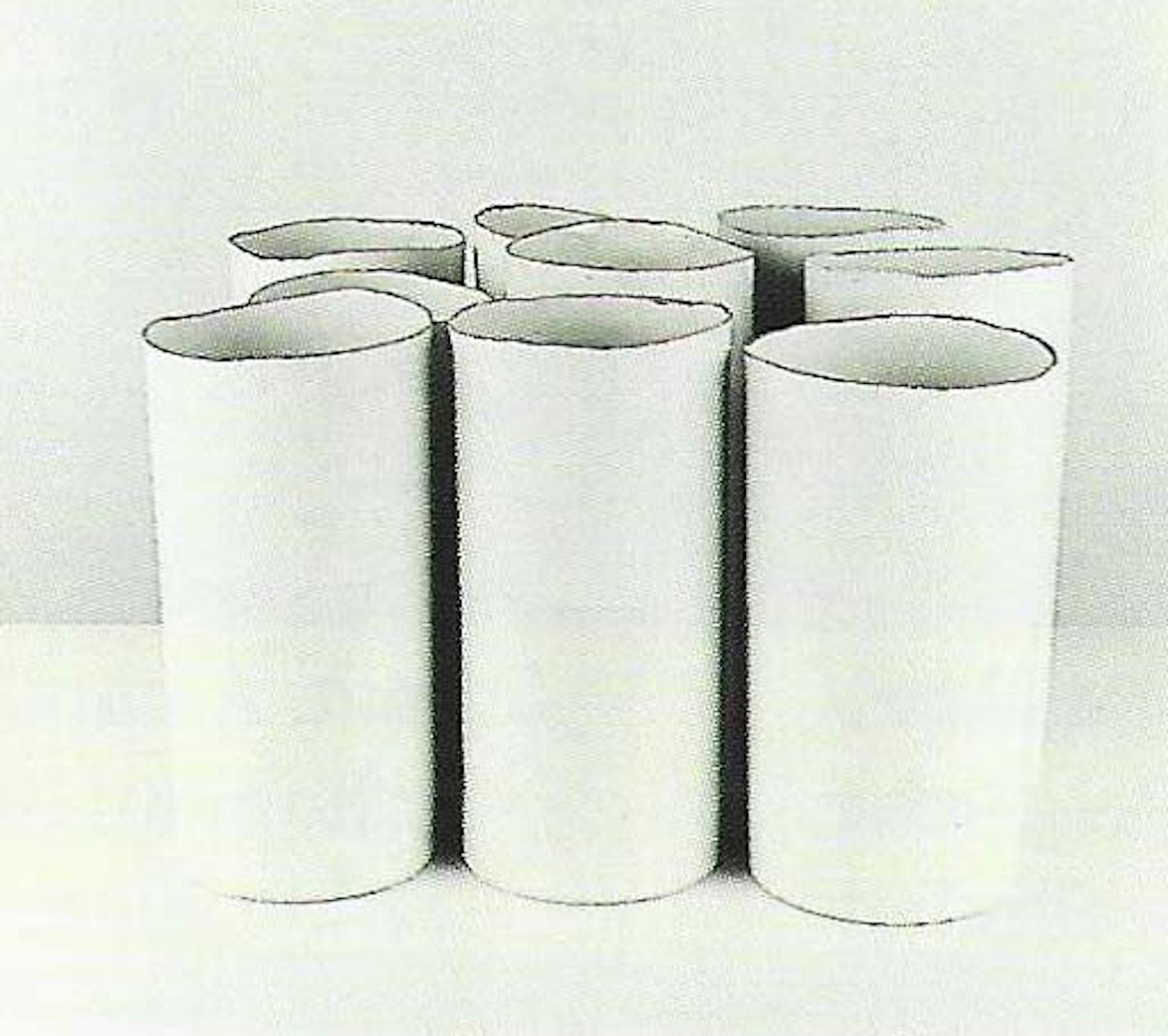

In certain works, the step taken from industrial to free work is more than evident. Examples are his series of vases dating from 1980 of which Stockmans made variants in 1987 and 1994. These were produced industrially and were intended as serial products (and therefore were also stamped). But because of the manual changes carried out during manufacture, the work also has a strong personal character.

There are indeed links between his industrial work on the one hand and his independent work on the other.

There is his preference for pure china, something he had learned to master as no one else during his training courses and experiments at Mosa. Piet Stockmans casts practically everything himself (the last few years he is helped by his assistant) and he gradually bakes it at 1410°C. He colours his pieces with industrial china glazes to which, at times, he adds some colour. He is the only one of his generation (1965-1980) who has been so consequent in his use of china.

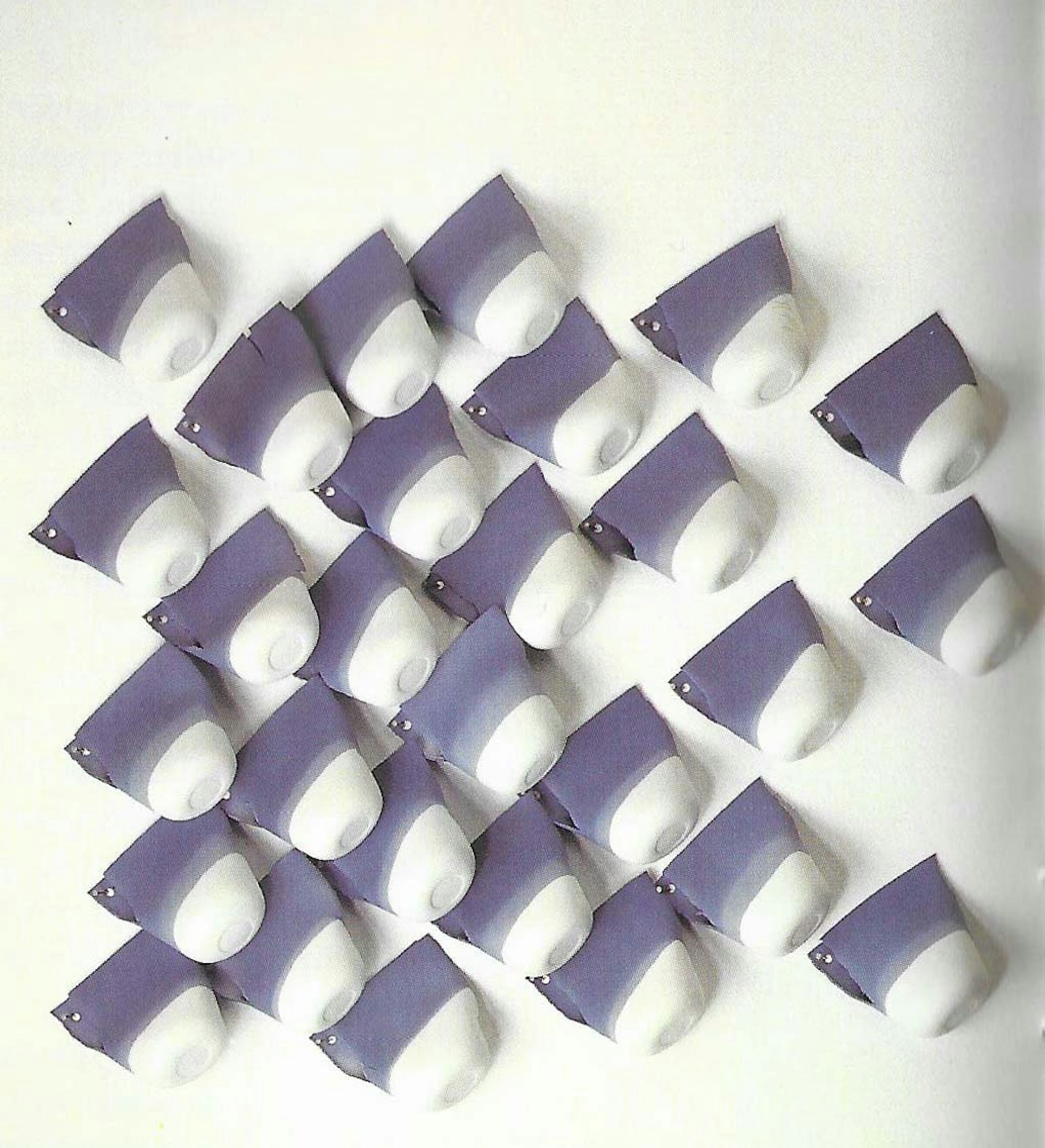

A second allusion to his industrial production in his free work is the emphatic presence of the serial aspect of manufacturing: the continuously recurring principle of quantity and repetition to which he so relentlessly opposed himself. From the eighties on, his china installations with their thousands of randomly arranged small dishes are all identical in form and still so different because of his subtle use of mainly blue colour glazes and powder and he removed each one from its plaster moulding by hand.

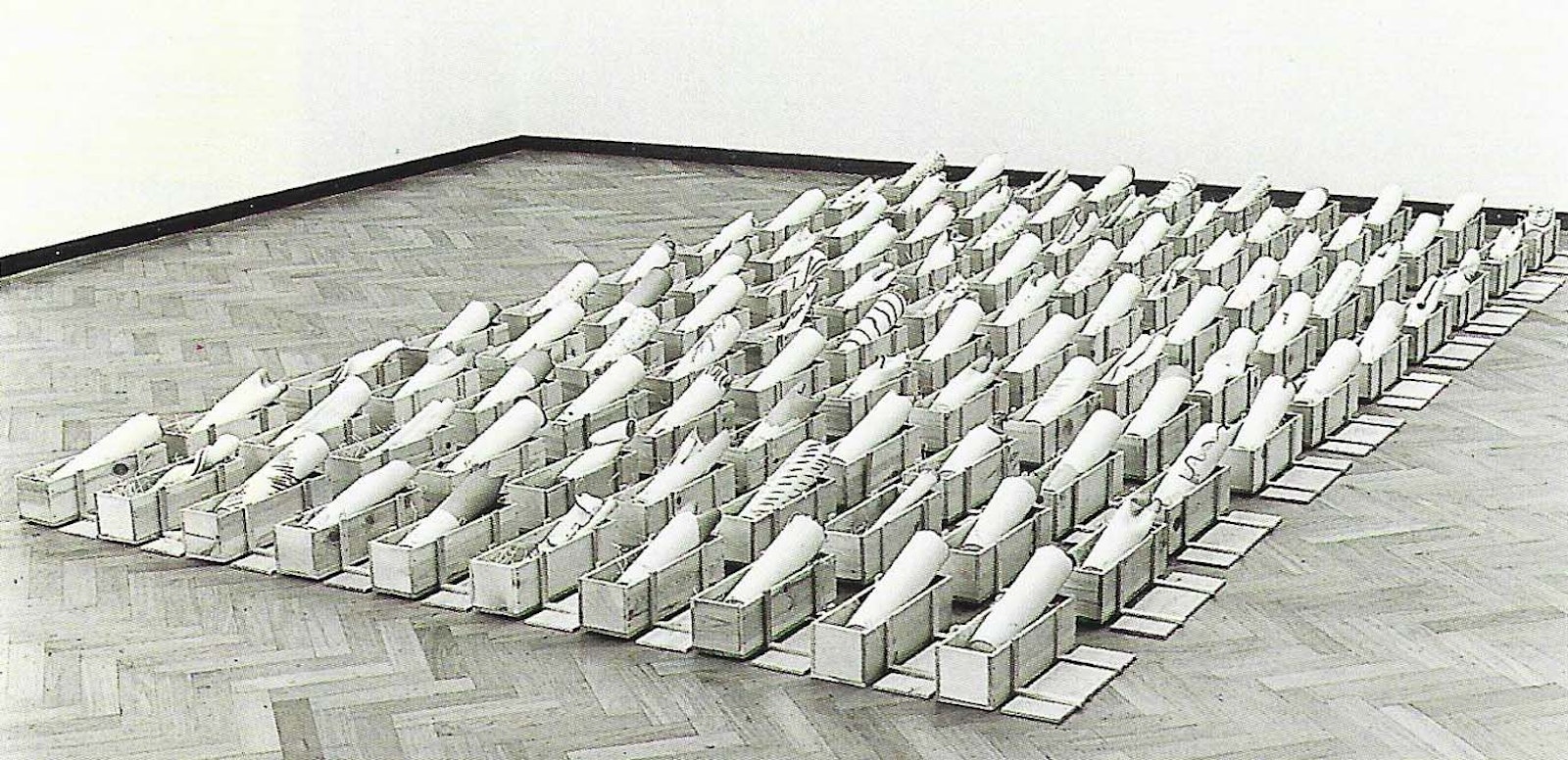

The effort involved in these numerous ritual unpackings and rhythmical set-ups is comforting to Stockmans. Later on — also because of the difficulties at his factory — this physical aspect became even stronger until he finally and almost aggressively rejected the functional by cutting, bending, painting, perforating and breaking the work.

Today, his installations consist of objects which do not always allude to utilities which he places or has emerging from boxes filled with straw. This change has come about organically. The boxes have always existed, but originally they only served to transport objects. In these installations, the objects are at the most only partly removed from their boxes which are now an integral part of the installation. Unpacking and storing the wrappings is no longer necessary, therefore. In the last four years, these objects have become masks: casts of his own face.

His two branches of activity should therefore not be considered as being separate, but rather as being the result of an interesting dialogue between the industrial designer and the artist, who are both brought together in one person. On the one hand, we have the industrial designer who works according to the rules imposed by industry, on the other we have the artist who reacts against this and renders useful items dysfunctional through his actions.