de Velde

Kristel Van Ael & Joannes Vandermeulen (Namahn)

Joannes founded Namahn in 1987 as a one-person consultancy in Brussels, helping companies to define, refine and improve their technology and software offerings towards end users.

"Kristel Van Ael and Joannes Vandermeulen are the founding partners of the Namahn design agency, specialised in human-centered design and one of the world’s leading agencies when it comes to digital, user experience and service design.

Kristel Van Ael and Joannes Vandermeulen complement each other very well as a team; they are prolific and quite mature in their design practice. They receive frequent attention from the international design community. The jury is of the opinion that the agency has yet to reach its growth potential and envisages continued international expansion, a day at a time.

Joannes Vandermeulen & Kristel Van Ael. From lightness to complexity

As the consultancy grew, Joannes was not content with only bringing innovation to clients. When Kristel joined in 2007, Namahn had made a name for Interaction Design for digital products (or to use common parlance, user experience) and was a leading supplier to clients both large and small across many industries. With Kristel’s arrival in 2007, Namahn gained its first outright ‘visual thinker’. She brought a new language and a new way of seeing. She provided a bridge to the design community and positioned Namahn towards that world at a time when designers were only just beginning to enter the digital arena.

Namahn has moved more and more towards designing solutions for complex and critical systems. Both Kristel and Joannes realized that their existing methodologies were unable to handle these new complexities. So they set about designing new ones.

Their goal is to do significant things for people, to do more and on a bigger scale.

The year is 2000. The occasion: John Thackara’s Doors of Perception international design conference in Amsterdam on the theme of Lightness. At this meeting of ecological and social systems and design minds, Joannes Vandermeulen and Kristel Van Ael recognize each other, not from a previous professional encounter but from their kids’ school gate in Brussels: “What are you doing here?”

To quote John Thackara: To do things differently, we need to see things differently. Not only did Joannes and Kristel see each other in a different light that day; their meeting led to new ways of doing things.

But not immediately. In fact, they were advised never to work together. Some warned of Kristel’s ‘stubbornness’, others of Joannes’ ‘craziness’. Kristel was deeply rooted in the design world, Joannes in the digital and computing world. Kristel’s language was most definitely visual, Joannes’ most definitely written. Namahn was not a ‘design’ agency but a provider of human-centred design for software interfaces. And yet… in 2007, the planets aligned and they joined forces as partners in Namahn.

Namahn celebrates 30 years of existence in 2017. But it could be argued (and as this award would suggest) that in the last eight years, under the partnership of Joannes and Kristel, it has achieved its full promise. That’s not to say that either of them weren’t successful operating apart. Rather, it’s as if until they collaborated, they had been rehearsing off stage for the main act.

Early days of interaction design

Joannes founded Namahn in 1987 as a one-person consultancy in Brussels, helping companies to define, refine and improve their technology and software offerings towards end users. This came after studies in Archaeology and Oriental Linguistics at KULeuven and a stint in the US working as an executive assistant, where he developed a fascination for computers and discovered a talent for writing. Most importantly, he observed a gap between what people need from computer technology and what they got. This was at a time when user-centred design (UCD) was just emerging and the digital revolution as yet unimagined.

As the consultancy grew, Joannes was not content with only bringing innovation to clients; he also wanted to adopt an innovative structure within: an open-book, equitable business model offering transparency, honesty, flexibility to all his collaborators, or ‘Namahni’ as they are known today. They practised the same openness towards clients, pioneering collaborative ways of working and co-creation. Before it became common practice, Joannes and his team were creating personas and conducting usability testing directly with users in their context of use and then relying on their expertise and experience to arrive at design conclusions based on what they saw users doing in situ.

When Kristel joined in 2007, Namahn had made a name for Interaction Design for digital products (or to use common parlance, user experience) and was a leading supplier to clients both large and small across many industries. Never content to sit still (literally and figuratively) Joannes was already pushing a new frontier, embarking on a two-year research project focusing on models, theories and frameworks applicable to the domain of Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) for safety-critical systems. After 20 years in the field, it was the perfect moment to leverage relationships developed over the years with the HCI academic community and practitioners and attempt to gap the bridge between theory and design practice.

Design in the service of others

Kristel has always been more interested in what good design could bring users as a service, rather than the ‘outside’ of the product. She studied Industrial Design in the 1980s, an era when ‘design’ was a big marketing word and designers were expected to deliver the differentiating ‘lifestyle’ selling factor, something that disappointed her from the start. Disenchanted, she began working for a marketing company, developing their design studio and cutting her teeth on the very first Mac SE 30. She went on to co-develop this studio into a 2D and 3D packaging design studio. Her next step was into the nascent world of web design, where she developed a passion for technology while making websites for the Flemish creative community, for musicians like Walter Hus and choreographers like Wim Vandekeybus, plus cultural events and associations. In 1997, three years before meeting Joannes in Amsterdam, she had what she describes as her eureka moment: attending The Human Village conference in Toronto, she heard speakers such as Maurice Strong (Chairman of the Earth Council Alliance), Paul Hawken (one of the environmental movement’s leading voices) and Oren Lyons (Faithkeeper of the Turtle Clan) call on designers to change their mindset, do things differently and collaborate as catalysts (and creators) of change for people and society.

Meeting of minds

With Kristel’s arrival in 2007, Namahn gained its first outright ‘visual thinker’. She brought a new language and a new way of seeing. She provided a bridge to the design community and positioned Namahn towards that world at a time when designers were only just beginning to enter the digital arena.

Namahn was still producing lengthy written reports and technical specifications with few if any visuals, a requirement of clients who needed convincing of their design rationale and as a guide to implementing their human-centred design recommendations. However, the world was changing and Kristel helped to accelerate this. Today, there is no need for documentation: it’s a case of ‘see and do’.

Their true meeting of minds is a love of complexity: Joannes’ stemming from a technical and functional career spent designing for complex systems and interfaces and Kristel’s, from a passion for designing socio-political change (ignited in 1997) and teaching Product-Service Systems design at Antwerp University. They both have a similar approach to their design prac - tice, grounded in models, theories and frameworks from academia, and both rely heavily on science, albeit in different ways: Joannes to understand the facts, Kristel to find inspiration.

They also share an appetite for understanding the interconnectedness of things. For them, design thinking is all about how you deal with failure, silos or decisions and how these things are intertwined. Last but not least, they are both motivated by a desire to be at the cusp of design thinking, to do things differently and to collaborate. As equal partners in Namahn (he focusing on business development, she on knowledge management) Joannes and Kristel demonstrate that greater things come from working together than can be achieved by working alone.

Capturing wisdom

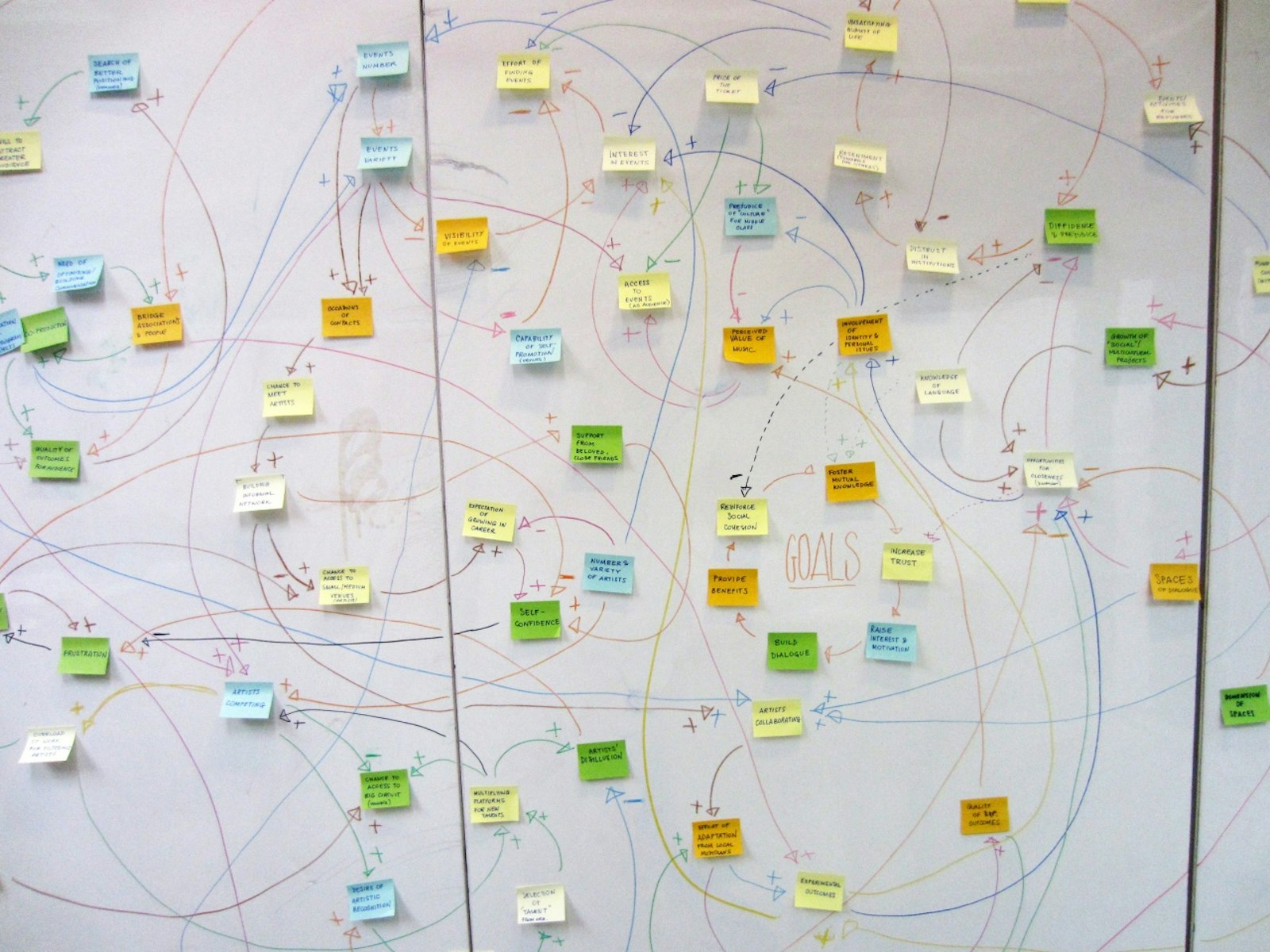

In 2010, they opened a design studio purely dedicated to co-creation in the Namahn building. This was conceived with the users in mind and was the first of its kind in Belgium. It effectively transformed the role of the designer into a facilitator, grounded in his/her empathy towards end users and all the stakeholders involved. This studio has become emblematic of how they conduct their business: knowledge sharing and collaboration with clients and fellow designers through multiple Namahn-led workshops.

In the intervening years, co-creation has become a buzzword. Namahn is already evolving to the next level, towards conversation, and from human-centred to people-centred design. Joannes and Kristel are deepening this further, asking themselves about the language they should use, the terminology, words, and vocabulary. If you want to change something, you need to change the language.

This level of collaboration does not work without empathy. Kristel, Joannes and their team are able to bring people together across silos, get them working together in new ways, engage them in creative conversations using techniques they invent and master, or in Kristel’s words, “to capture the wisdom of all the people in the room, their perspectives, contexts and needs” and then harvest the ingredients for a design.

Both sides of a paradox

Namahn has moved more and more towards designing solutions for complex and critical systems. Both Kristel and Joannes realized that their existing methodologies were unable to handle these new complexities. So they set about designing new ones.

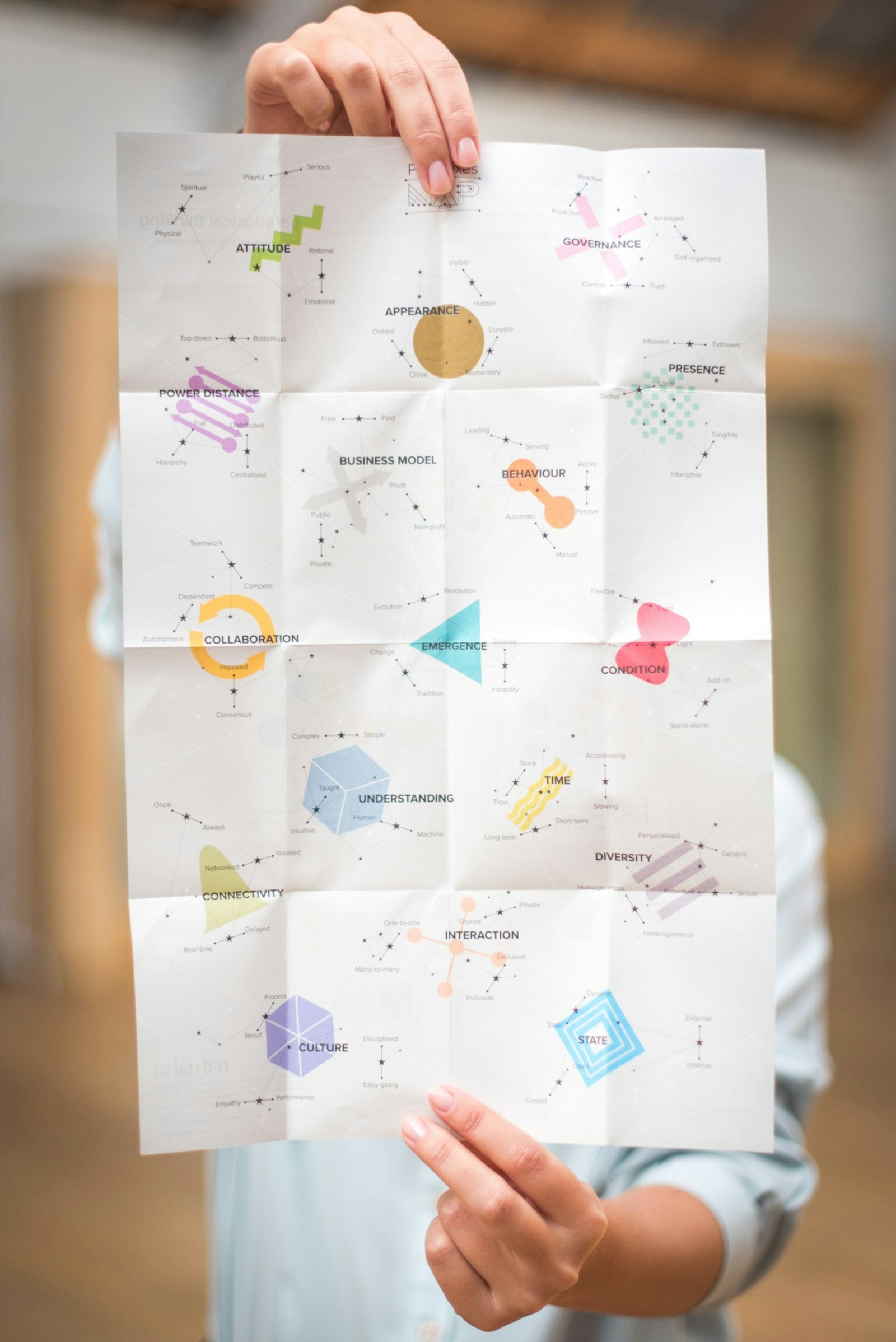

In the past eight years, a portfolio of visual tools and methodologies has emerged, including a Service Design Toolkit, Human Drive cards and collaboration on a guide to Public Service design. Amongst other domains, Kristel finds inspiration in quantum physics and cybernetics, although she claims inspiration can just as easily come from a cookbook or a graphic novel. The purpose is not to be scientifically right. Currently in development is a Systemic Design methodology, capable of handling complexity and predictability. In a world where only a handful of designers are actively interested in Systems Thinking, this is again pioneering.

In 2016, Paradox Cards were added to this portfolio. The idea was sparked by an article Joannes shared with Kristel on Paradoxical Thinking from the Harvard Business Review, which suggested that advanced designers always think in terms of paradoxes and intuitively try to solve the extremes of paradoxes without compromise. In contrast, non- or starting designers tend to solve only one of the extremes. Since complex or critical systems contain a lot of paradoxes, it becomes all the more essential to address these when designing for the end. These cards help Namahn and its clients to discover, think and talk about the existence of paradoxes in their organization, product or service. They help to ensure that designers design consciously.

Namahn culture

This story is not complete without mentioning the Namahn culture. Besides its open management style and flat hierarchy, the way the company collaborates, collects and generously shares knowledge and physical space with colleagues, clients and the wider community in which it is embedded in central Brussels, is unique.

This open culture embraces creative spirits such as the Belgian composer in residence Walter Hus plus performing artists. Regular Namahn lectures are a unique (and free) opportunity to hear world-leading speakers from a wide range of disciplines. These sessions in the well-stocked Namahn library make a serious contribution to the continuous opening up of design thinking horizons in Belgium, and have welcomed renowned names such as the systems thinker Philippe Vandenbroeck, the primatologist Frans De Waal and, to complete the circle, John Thackara himself.

Joannes and Kristel highly value the fact that they have created an organization they like, which is fun for them and for others. Both see the act of welcoming new streams of talented and smart people as a privilege. This community is something precious, a well-functioning family, where things don’t need explaining but are intuitively understood. Read the profiles on the Namahn website and you’ll understand.

Designing the future

Is this the right place for us to intervene? Will it make life better for people? What is the underlying problem? You need a certain level of maturity to listen, understand and know where and when to intervene as a designer in order to benefit an organization and its people. Kristel and Joannes have probably reached this point.

According to them, designing the future will require being extremely open-minded, ready to accept different worldviews and respect, understand, and appreciate the complexity, not deny it. Their goal is to do significant things for people, to do more and on a bigger scale. In light of recent world events, I find Kristel’s closing observation particularly apt: “Why can’t we as a design community redesign the democratic system?”

I am convinced that if anyone could have a good crack at this, it would be the winners of the 2016 Henry van de Velde Lifetime Achievement Award.