de Velde

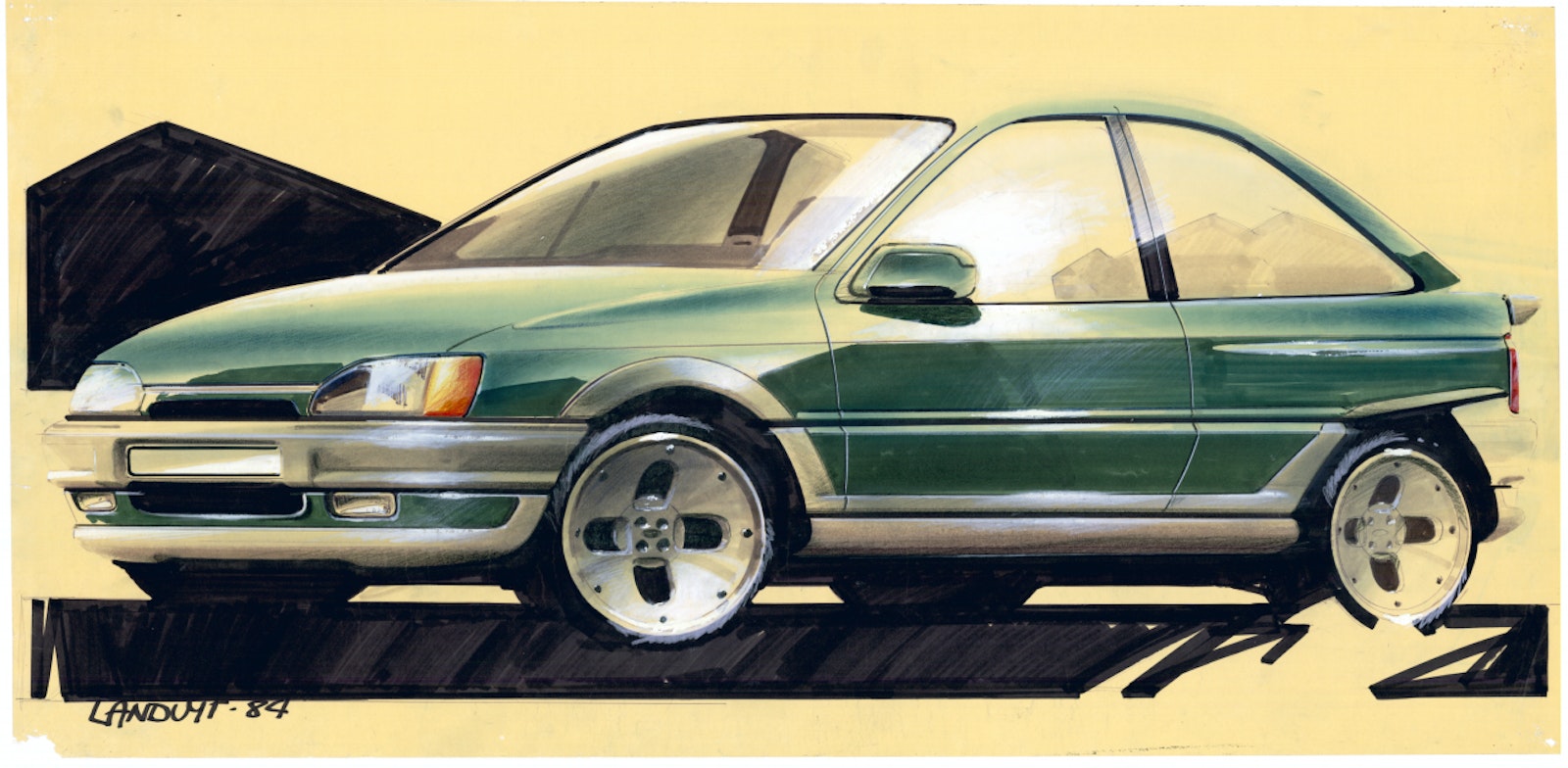

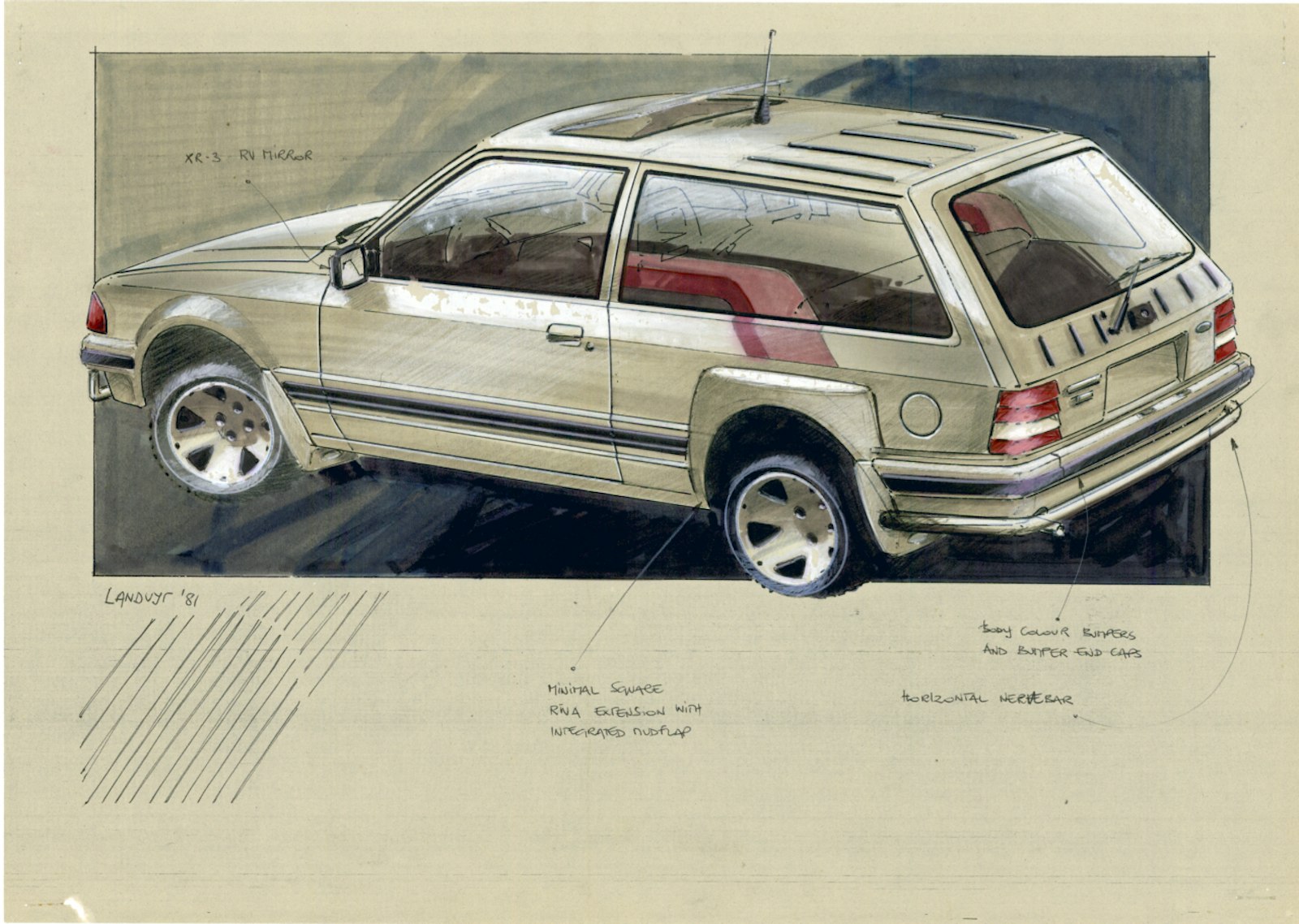

Luc Landuyt

Luc Landuyt (b.1948) has enjoyed a fine career as a car designer.

Some say he is the first car designer to come from Belgium, but he says that he isn’t because there were about seventy automobile companies in Belgium in the early 20th century. They may not have produced large volumes and they mostly made trucks, or other functional transport vehicles, but they did all employ designers, although they weren’t called designers at the time.

“So I’m not the first Belgian car designer, but I am the first Belgian to study car design. I got my BA in Industrial Design from the Henry van de Velde Institute in Antwerp in 1974, and went on, after my military service, to study at the Royal College of Art in London, without a grant. It was a very tough selection process, but my portfolio went down well; I was admitted as a student and, in 1979, I got my “MDesRCA Automotive Design” (editor’s note: Master in Design). As the first Belgian to pocket that qualification I helped inspire other young people to become car designers, and that is important to me,” he says.

An interview in the Belgian magazine Knack Weekend revealed a great deal. “Young guys came to realise it was not impossible for a Belgian to become a car designer. And that, apparently, is how I’ve been instrumental in helping a few people make their dreams come true.”

At Ford, which he joined in 1979, he would regularly receive drawings from up and coming designers, several of whom he helped to actually find design jobs, including Mario Polla and, of course, Dirk Van Braeckel. “Dirk was a go-getter,” Landuyt tells us. “When Ford gave a few of the young employees in the design department the opportunity to showcase their talents as designers, Dirk was the only candidate with the self discipline to develop a good portfolio. In return, Ford funded his studies at the Royal College of Art.”

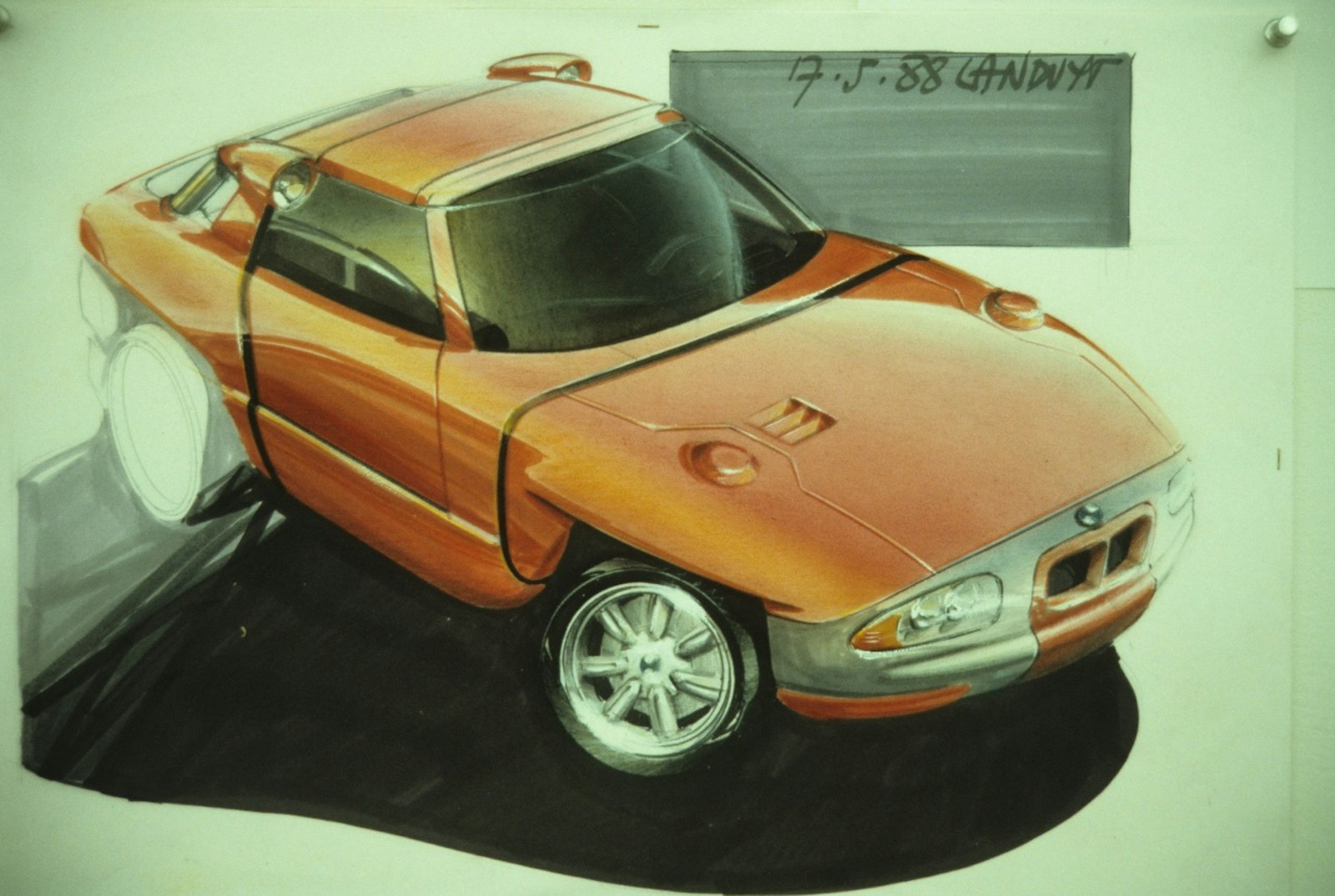

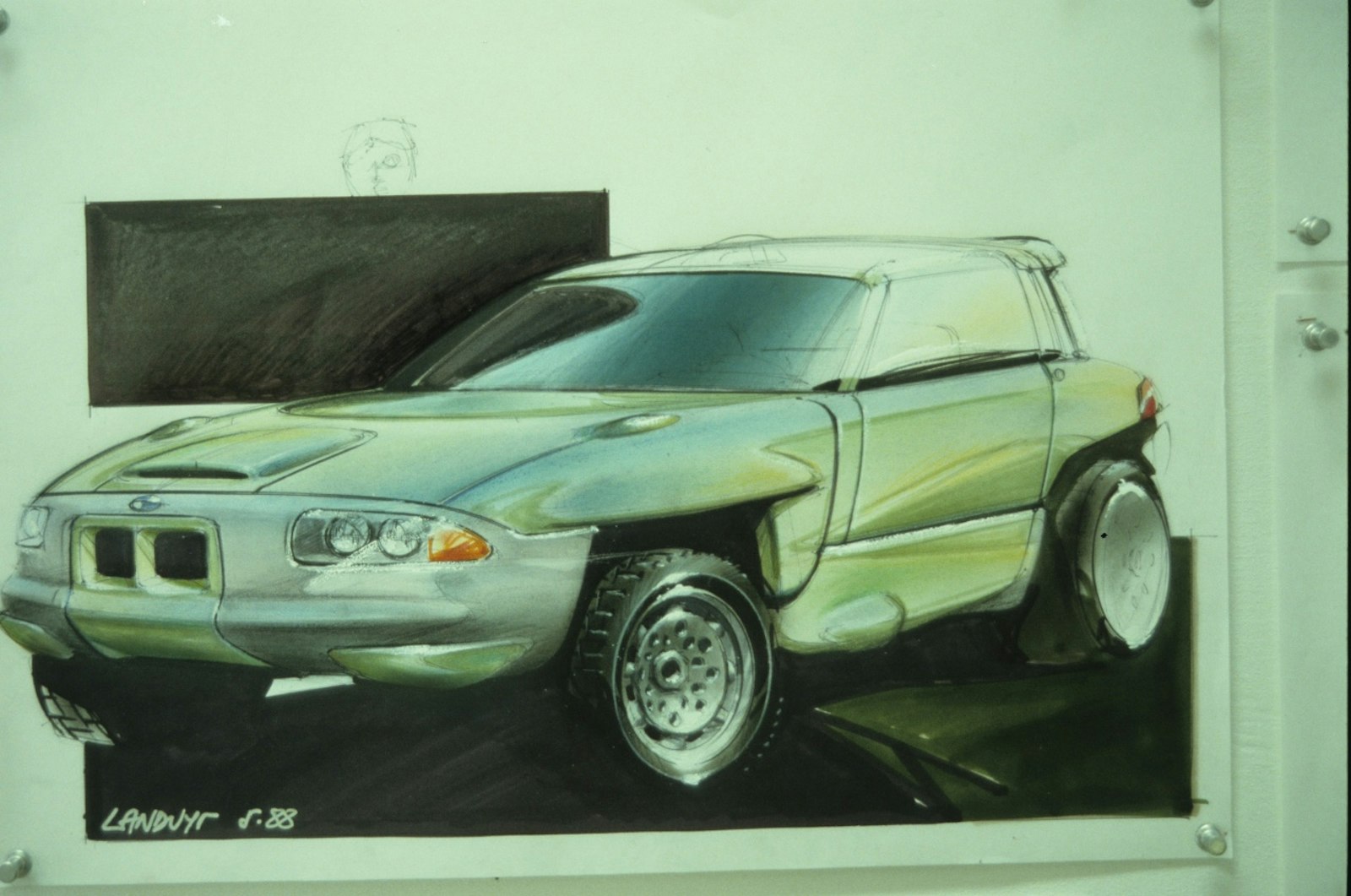

But, aside from the Belgians working for Renault, he actually knows very few Belgian designers personally. When, in 1985, there were rumours that Ford’s “Exterior Design” department was moving to England, Landuyt relocated to BMW (1985–1992) where, for BMW Technik GmbH, he designed the BMW Z1 and other models. He has worked for Renault since 1992, who seconded him to Nissan in Japan from 1999 to 2002. In 2002, he returned to France, where he became the “Design Director” for Small Car Programs, for Large Car Programs and finally for Advanced Design.

On 20 September, I went to Versailles to meet this modest, softly spoken designer. We met a stone’s throw from the world famous palace of Louis XIV. Landuyt’s lovely wife came to pick me up from Paris Nord and guide me through the Parisian maze of metros and regional express networks. It was only with her help that we were able to get to the appointment on time.

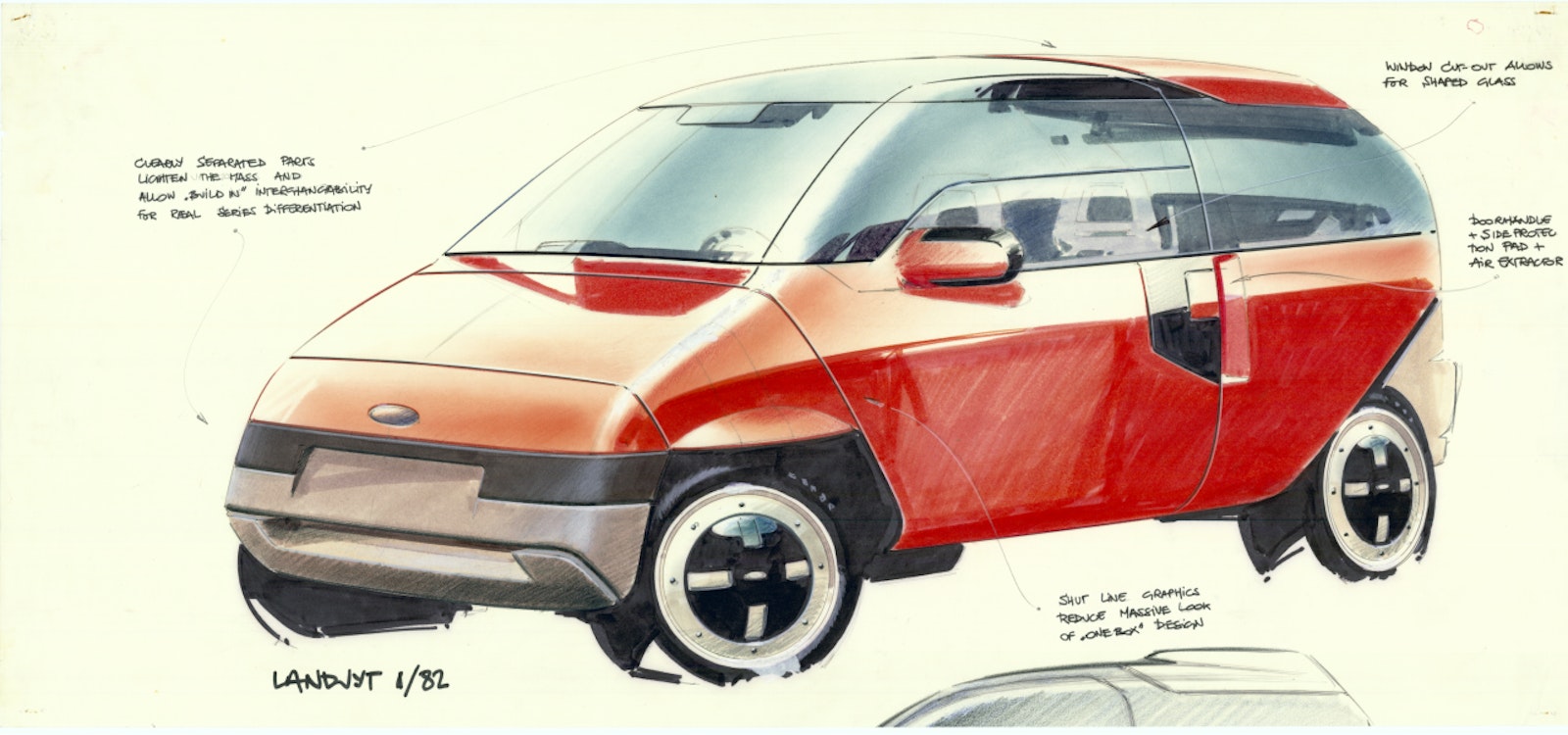

We talked about the modern perception of the car. On the one hand, according to Victor Papanek (1923–1998), designer and advocate of socially responsible design and, judging by the road safety statistics, the car is a deadly weapon but, on the other, it is a piece of machinery that can serve us in so many ways, and this is the perfect challenge for the designer. Luc Landuyt sees it on two levels. “On the one hand, you can accommodate as many people as possible,” he believes, “by designing a product that respects the quality of the environment, the air, the notion of mobility, and one that people like and that gives them a good feeling. On the other hand, you can, as a designer, ignore that whole concept, go purely with your passions and design cars that are bound by no preconditions whatsoever. I always sought my place in the first category: to design ‘made to measure’ cars, with economical engines, that are affordable, or even electric."

"BMW’s E1 was one of the first electric cars of this kind, as far back as 1990, and they brought out a second version the following year. The car was okay, but the weak point was its battery. It was a high temperature battery, originally for military use, with an operating temperature of about 350 degrees. Obviously, a system of this type is difficult to incorporate in a small car and it poses a high safety risk. The motor was okay, the thing drove perfectly well, but the configuration was far from optimal due to that battery. Car manufacturers can’t just start designing their own batteries. It is not among their core competencies. And even if they wanted to, the production volumes would be too small to make it economically viable.”

Landuyt wonders whether the future really is the electric car. He calls to mind a study, about ten years ago, which compared the ecological footprints of the Hummer and the Prius, and found that, because of the batteries, the Hummer came out with a better score. The full lifecycle of the battery, from the extraction of the ores to the difficulties of recycling, still presents a serious problem.

On top of that, you need a supply of power to recharge the batteries and, if a significant portion of the fleet converts to electricity, you need to think about the future and distribution of this energy form. “The whole of society revolves around oil,” he says, “and it would be a pity not only for the car driver, but for everyone else, if we were to lose it. No oil would mean the end for an inconceivable number of products. Today, the whole of our material world is built around oil. We will have to ask ourselves whether it is financially, ecologically and economically feasible to continue to extract oil, and indeed identify the things that we would continue using that energy form for.”

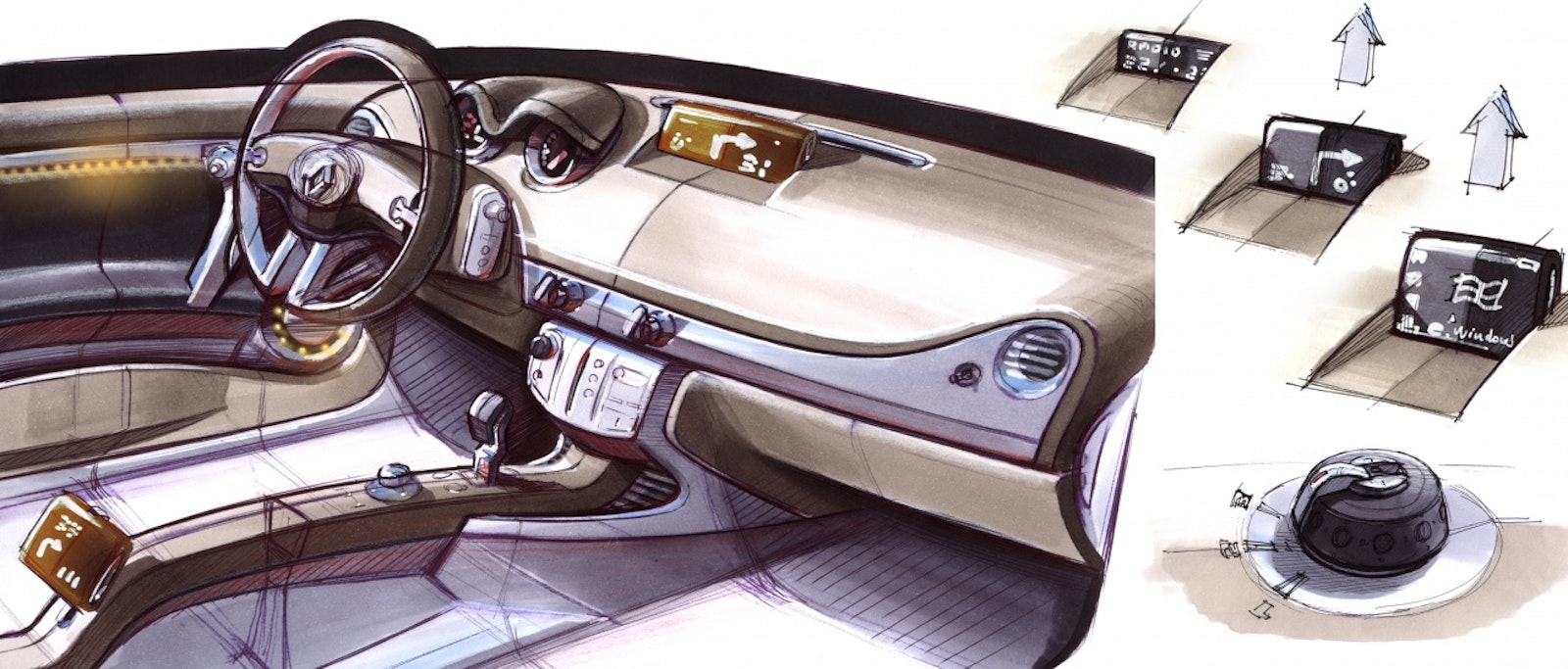

When we get onto the subject of the latest trend in service design, he tells us that the car brings with it a number of risks. The car is not a static object. The driver’s attention – while using the car – is almost exclusively devoted to “driving”. “Service” should be provided in an extremely ergonomic way, and that is becoming more difficult given the number of functions in the modern car. The way in which information is given and requested is an extremely important matter and cannot conflict with the issue of safety.

But that’s not all! The designer has to translate, at all the right levels, the whole emotional aspect that is still associated with cars and “driving”. The emotional aspect must “sublimate the functional aspects”, but not compete with them. This is true for the bodywork, the accessories, the dashboard, the seats, etc. The outward appearance is fundamental because the main reason for anyone buying a product is the look of the thing. Of equal importance is what the car says about the buyer. Status, image, etc. Car makes that already have these properties, such as Mercedes, Audi or BMW, are very often at the top of the wish list. Also, the customer is often motivated by a feeling of how well the car ties in with his or her self image. And if you want to make use of this you, need a very good understanding of who your car is intended for. It takes a really long time to build a strong image, and, in addition to the car’s look and functional aspects, it requires a mass of (technical) service and content.

Design, however fundamental, determines more than just the image. There are a great many people who exert an influence at every stage of a car’s design and construction, and this influence is often beyond the reach of the designer. If it sets itself a clear strategy, however, a make can respond quickly

to the competition and trends. To the question of how fundamental the designer’s contribution actually is, he answers: “Above all, the designer listens to what is happening around him. A car built without a designer will probably drive. It will be comfortable and ergonomic. Many other aspects will be sorted, too, because all kinds of experts contribute to the process. But whether or not that car will look good, or feel nice (‘touch design’), or give off a strong personality is another question. Anyone can draught a 2CV and it is easy to decide whether a car should be big or small, but not everyone can design a beautiful car,” he tells us.

The course he studied in Antwerp had been set up by graduates from the Ulm school, the successor of Bauhaus, who assumed that designers could change the world and make it a better place. That message was unfortunately lost in the seventies and eighties and design became a marketing instrument. The “real world” of Victor Papanek looked different to what it was when he wrote his book. Perhaps we have returned to a situation today in which the social responsibility of the designer is coming - or ought to be coming - to the fore.

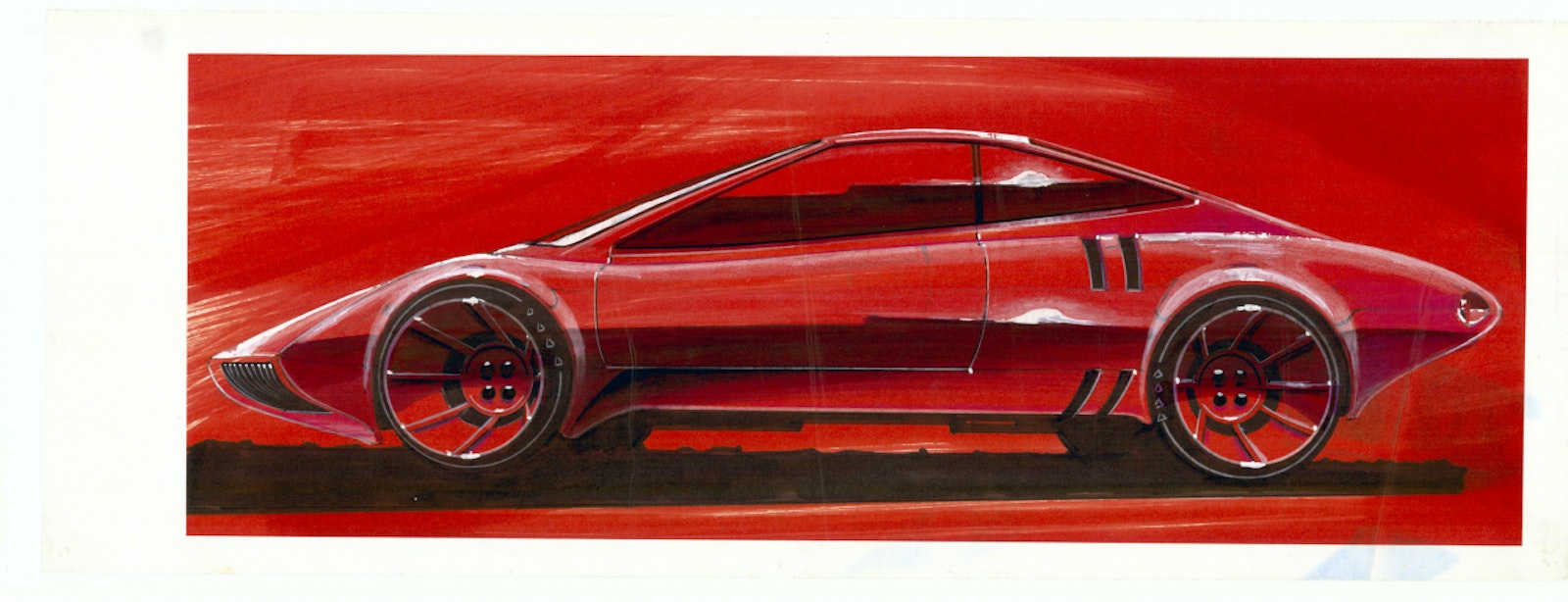

He wrestles with the question of why “we” still allow the design of cars that can reach speeds of 350 km per hour, whereas the maximum speed in most countries is 120 km per hour. “If a car ‘is a deadly weapon’ (Papanek), then why are these things still for sale? Weapons are subject to very strict regulation,” he says, “and their sale all but banned. In that sense, allowing the construction and sale of very fast cars is, first and foremost, a political choice. Of course, a designer or manufacturer can take some degree of social responsibility and choose, for example, to design nothing but electric cars ... or bikes. But if you’ve got ‘petrol in the blood’ and want to work in the automobile industry, these choices are not as easy as they look. You can try to be as politically correct as you can and work for popular makes, such as Renault and Ford. There, you can expect to work on more acceptable products. At BMW Technik GmbH, I had the good fortune of being in a think tank, where they gave capital letters to concepts like the green economy and social responsibility. Some of the cars that they designed could indeed do 250 km/h, but a great deal of attention was paid to safety, recycling, the quality of the environment, etc. It was all in the right direction ... A car is not really the ideal way to improve society, but once you have come to understand this, you can decide that you will work hard towards making the product as good as it can be. And... in my ‘wicked’ profession

I have always tried to design objects with the biggest possible ‘total user benefit’ and smallest possible ‘ecological footprint’.”

His great passion is still for Italian cars. His favourite is Zagato, the famed coachbuilder associated with Alfa, Ferrari, etc. His teenage dream to work in Italy came true very late in life when, in 2012, Renault sent him to Cecomp in Turin for eight months, on one of the LCI future projects. A little known fact is that this firm builds prototypes for quite a few manufacturers. They also produce the Bolloré, the electric car used for Autolib’ car sharing in Paris. And, the cherry on the cake, they model almost all of the Zagato projects! ... Cecomp are real “coachbuilders” who have partnered all the main Italian design houses, although their biggest client today is Toyota.

At the end of the interview, he says in his dulcet tone that his hobby is restoring old motorcycles, all pre-war 100 cc Motobécanes ... he has three in his living room, but owns eight altogether. “Fortunately, he now has a big shed,” adds Mrs Landuyt, who has been following the interview keenly. We part ways and, in his strikingly modest tone, Luc says: “It wouldn’t offend me, either, to be compared to an artist.”